The other day I heard a comment (second hand) that a trail user made about the latest reroute we are installing on the Imperial Trail in Greenhorn. He said, “I don’t need a lollipop handed to me when I ride Imperial.” In other words, by rerouting this section of the trail into a sustainable alignment we were making the route too easy, less interesting, and less fun for this person. Some people call such reroutes the “dumbing-down” of a trail, or the “homogenization” or “sanitization” of a trail. Such labels seem to demean the efforts being made to keep the trails in good shape and open, but it’s important that we don’t take such comments personally. Rather, we should consider them as constructive criticism, and when we do work to improve the sustainability of our trails, we should challenge ourselves to make sure that we do everything we can to preserve their iconic nature.

We need to be careful that our trails don’t eventually start to become much the same in character. We want a rich variety of trail experiences, not a milk-toast type of trail network where one trail is just like the other. Being sensitive to these concerns means that we need to work harder to ensure that we don’t make the trails all alike.

Its certainly not our intention to make the trails we work on less appealing to trail users. Actually, we are trying to do just the opposite. Trails that require a lot of maintenance are usually not very desirable routes. By putting the trail into a position on the landscape where it will hold up well, we are hoping that more people will come to enjoy it.

This summer I’ve worked with the Ketchum Ranger District on re-alignments in the Greenhorn and Imperial drainages; areas impacted heavily by last year’s Beaver Creek Fire. It has been important to get repairs made quickly in order to minimize the damage that is occurring as a result of erosion, and to get the trails reopened to the pubic as soon as possible. In such situations, trail reroutes are very useful tools.

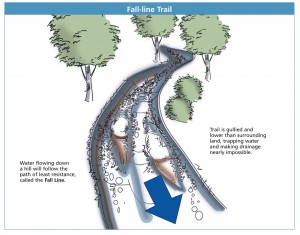

Often, our most problematic trail alignments are those that are in the fall line, or which approach a fall line alignment. What do I mean when I suggest that a trail is in, or approaching, a fall line alignment?

The fall line of a hill is the steepest path down that hill. If you were to roll a bowling ball down a hill it would, generally speaking, follow the fall line of the hill as it heads down the slope. This is the path that water will follow when it flows on the landscape. If a trail is in the fall line, or approaching a fall line alignment, water cannot be drained from the trail because there is no lower land adjacent to the trail where water can be drained.

Usually, trails being rerouted have been worked on many times in efforts to make them more sustainable. If you look at the trails that are being rerouted they are often filled with old check dams that have failed to deliver on there intended purpose.

Check dams are logs or rocks that have been laid perpendicularly into the trail tread. They are dug in deeply enough to hold them in position, while leaving enough of the structure exposed above grade to help form “dams” to slow the flow of running water. Besides helping to hold the trail in place, these structures create an area behind the check dam where soils and sediments are deposited once the flow of water is slowed. Check dams temporarily stabilize the trail and help keep soil from being washed away quickly.

Check dams can provide a short-term repair to fall line trails, but in time, water undermines the dams and they no longer function as intended. When this happens larger check dams need to be installed, or another approach to the trail’s maintenance needs to be employed.

Over time, fall line trails, with or without check dams installed in them, get deeper and more incised. They tend to take on a pronounced “V”, or “U” shape. As they get deeper they become increasingly difficult to negotiate on foot, bike, or horseback. Once a trail becomes incised, trail-users find it tempting to climb out of the ditch-like conditions onto the higher ground found adjacent to the trail. Soon, multiple alternative trails get burned-in alongside the existing route. These “braided” trail conditions create an even bigger maintenance concern because eventually the entire hillside is covered by redundant fall line trails, none of which can be maintained in a useful condition.

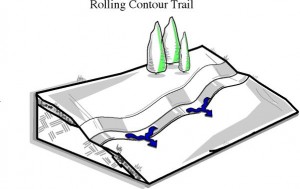

When we reroute a trail out of the fall line we look to reposition it into a rolling contour alignment. Such trails follow along the contours of hillsides; they don’t go directly up or down hills. Changes in grade are accomplished more gradually.

A contouring trail has land adjacent to it that is lower than the trail itself. This provides opportunities where flowing water can be drained frequently from the trail. This dividing of the trail’s watershed into several smaller drainages helps us avoids situations where large volumes of water are allowed to collect and flow on the trail.

When we reroute a steep fall line trail into a sustainable alignment we try hard to keep the new route as demanding, and as interesting, as possible. We aren’t trying to change your whole-wheat baguette into a piece of Wonder bread; we’re simply trying to keep the trail on the hillside without resorting to paving the route.

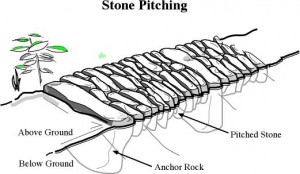

What about paving the route? It is possible to pave, or “armor”, fall line sections of trail with rock, but such armoring is expensive and time consuming. This type of an option can be more affordable if rock suitable for the armoring is available trailside.

We should carefully weigh the costs and benefits of armoring trails versus building reroutes. Among the questions we should ask are:

- Is such work possible with the limited budgets our land managers are working with?

- Will such constructions keep our trails functioning well in their current alignments and will trail users stay on the armored sections of trails?

- Will the results be welcomed by a broad cross-section of the public, or will many find such paving projects out of character with our cherished local trail experiences?

In a way, it all comes down to what we want, and how willing we are to support efforts toward making the desired results happen. Is our community interested in seeing more ambitious fixes employed in the resolving of our trail sustainability issues, and will these be seen as the best approach in the long run? Hard to say, but in the mean time, it’s important for our community to know that our efforts at fixing maintenance issues on our trails are not designed to dumb-down the trails. We’re not trying to hand you a lollipop, were simply using the resources we have available to us in our efforts to keep the trails open and functioning well.

2 comments for “Don’t Hand Me a Lollipop”